Introduction

Our world faces major challenges. The negative impacts that arise from biodiversity loss and climate change are felt by nature and people across the globe. As the number of natural disasters increases, pandemics rise, extreme weather conditions intensify, the wildlife and other species decline. Unsustainable agriculture, mining and generation of energy lead to deforestation, pollution and overexploitation of natural resources.

Healthy nature and ecosystems are key for human well-being and development. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have been set up to counter the challenges we face. Yet, as the World Economic Forum points out there is a US$2.5 trillion investment gap per year, as only US$1.4 trillion of the required US$3.9 trillion is invested each year to reach the SDGs by 2030.

For preserving and restoring ecosystems alone, the required investment is estimated between US$300 billion to US$400 billion, whereas, only US$52 billion is being invested in such projects.

With the money contributed by governments and philanthropy only, we shall never be able to fill this funding gap. Some asset managers and conservation experts have suggested that the private sector could close more than half of this funding gap by setting up profitable enterprises with a positive impact. Yet, the private sector perceives nature conservation projects as relatively unattractive due to lack of availability of large-scale opportunities, relative illiquid nature of investment opportunities, the unconventional nature of risks, relatively low returns and long-time horizons.

Bankable Nature Solutions (BNS) have the potential to shift the existing perception of nature of conservation projects. BNS are financially viable projects which support the development of more climate-resilient and sustainable landscapes and economies. Their bankability enables projects to accelerate scaling and replication, realizing the large-scale positive impact on nature and communities.

Building conservation and nature-based solutions into projects represents a massive opportunity. We need to work with companies, financial institutions and local stakeholders to develop BNS. This way, we can deliver impacts that reduce pressure on ecosystems, drive resilience and sustainability for both People and Nature, while generating positive financial returns for communities and investors.

What is a Bankable Nature Solution?

It is important to have a common understanding of what Bankable Nature Solutions are, before working with them. While there is no single definition, there is agreement about their main characteristics. Bankable Nature Solutions (BNS):

- create positive environmental returns leading to positive biodiversity impacts or climate mitigation and/or adaptation; and

- are acceptable to investors as they have (a combination of) characteristics such as:

» Cashflow generating activities;

» Sufficient collateral;

» A high probability of success;

» A clear exit strategy;

» An acceptable risk-adjusted rate of return; and

» A clear proof of concept and proven track record.

Thus, BNS are solutions for environmental challenges that at the same time generate an acceptable (risk-adjusted) return on the money invested.

BNS are not just different from regular conservation projects because of their source of funding. They are intrinsically different as they are managed by the private sector and as their design is centered around revenue-generating activities that help recover project costs and generate a return on investment. BNS can be found across different themes – such as climate-smart agriculture, environmental protection, forestry, water and sanitation, and renewable energy. Compared to conventional (grantdriven) environmental projects, there is not only money flowing into a project, but the project itself also generates sufficient money to pay back investors and generate a positive return.

The investment can be through debt, equity or a combination of both. Hence, a bankable project is not an extra influx of money that can be used in the same way as when receiving grants.

For BNS to function optimally, it is of great benefit to focus on the wider landscape. The landscape approach is about reconciling competing natural resources demands in a way that is best for human well-being and the environment. More specifically, it seeks to integrate conservation, sustainable use and, where necessary, restoration across a landscape mosaic to sustain biodiversity and ecosystem services, whilst ensuring room for subsistence and commercial activities. It focuses on tackling issues together, which no individual stakeholder can solve alone, with the ultimate goal of achieving sustainable landscapes that help to meet the UN SDGs. It acknowledges the complexity in a landscape, provides flexible solutions to adapt to change and integrates multiple objectives for the best results. The landscape approach looks beyond individual projects, creating an enabling environment at scale to attract investors and to support the sustainable financing of landscapes. The Little Sustainable Landscapes Book (2016) has identified three important catalysts to enable integrated landscape management. These include: good governance, market access and sustainable finance. Five essential elements of a landscape approach are:

a) Establishing a multi-stakeholder platform

There are numerous stakeholders involved in a certain landscape, each with different needs and interests. Their views will not always coincide. Negotiation and trade-offs are therefore a key part of the process of realizing sustainable landscapes. Establishing and facilitating equitable exchange and communication between these stakeholders is thereby critical. The starting point is to identify the various interest groups involved and to find ways in which they can meet and interact in a just and effective way.

b) Building shared understanding

To build future pathways together, various stakeholders need to develop a common understanding of the issues in the landscape, the various interests, and the spatial interrelations. It is key to ensure that everyone has access to the same information to make informed decisions about management approaches for a sustainable landscape. The starting point is to assess the natural and social capital in a landscape and to identify longer-term trends and root causes of the issues identified.

c) Collaborative planning

Sharing a common understanding of the issues in a landscape and the diverse motivations helps to identify a negotiated landscape vision with multifunctional objectives. Creating integrated spatial planning helps to guide stakeholders on how to achieve the landscape vision. This includes a detailed action plan to put these objectives into practice.

d) Effective implementation

Many well-meaning projects fail because of a lack of focus on the implementation phase. During this phase, there might not be enough time and resources, or the right skillset may not be present. Landscape-level programs are designed for the long-term and therefore need to be secured from changes in government, donor, corporate or NGO policy to ensure sustainability. For carrying out the work plan, it is crucial to plan realistically, follow rigorously, and monitor carefully. At the same time, these plans need to be adaptive to cope with unforeseen events.

e) Monitoring for adaptive management and accountability

Landscape processes are dynamic. We must learn from changes to improve decision-making and management. A good monitoring program proves to be one of the strongest indicators for a project’s success. It helps to keep the momentum going by showing the impact realized and identifying when things are not working as planned and changes are needed. Monitoring costs are expected to be about 5-10% of the overall budget.

Bankable Nature Solutions in Action

The Mekong Delta, home to 17 million people in Vietnam, is one of the world’s most productive ecosystems with two to three rice crops a year and more than 450 different species of fish. At the same time, it is one of the regions in the world most vulnerable to water and climate disasters. Intensification of human activities and climate change across the entire river basin in six countries have altered natural water and sediment flows. In addition, land and water use within the delta are affecting its ability to cope. As a result, the delta is sinking and shrinking.

The erosion of the riverbed is aggravating saltwater intrusion – sometimes reaching up to 130 km inland – affecting soil fertility and poisoning crops. Land subsidence, aggravated by both groundwater extraction and loss of sediment deposition in the floodplains, make large areas of the delta increasingly more vulnerable to drought and floods.

With the aim to contribute to supporting Vietnam’s response to this urgent and massive challenge, WWF and the Dutch Fund for Climate and Development initiated the Mekong Delta Integrated Rice and Aquaculture Project. The vision has been to build a more sustainable and climate-resilient food production model for people, nature and businesses; a model that addresses root causes, is innovative, financially viable and can be scaled up and replicated in other Asian river deltas.

“The Mekong Delta, home to 17 million people in Vietnam, is one of the world’s most productive ecosystems with two to three rice crops a year and more than 450 different species of fish.”

Rice and Shrimp pilot

The project will be implemented at five sites with different conditions. It started in Ca Mau Province, the most southern part of the Mekong, in August with the conversion of 30 to 50 hectares. During the one-year test phase, 110 hectares of sixty farmers will be converted.

Following proof of concept, Minh Phu is seeking a €35 million ten-year loan to implement the full project from the second quarter of 2022. With the help of its partners, it will introduce the new way of farming on 30,000 hectares by 2028. But Minh Phu’s ambitions are much bigger than that.

Other partners in the project are TV Food Company Ltd., a rice exporter, the Vietnamese local government of three provinces and Deltares, a leading Dutch applied research institute into deltas. Their co-funding takes the total project budget to €800K.

From monoculture to mixed rice-shrimp aquaculture ponds

In the original model, farmers cultivated rice as an intense monoculture on one part of their land and shrimp on the other. Diseases spread easily and the high use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides and antibiotics killed all biodiversity. Meanwhile, the farms became more and more vulnerable to droughts and the intrusion of salt into their land.

To create a climate-resilient landscape (in line with the Vietnamese government’s climate plan), the Mekong Delta Integrated Rice and Aquaculture Project has designed mixed rice-shrimp aquaculture ponds. The ponds produce rice and freshwater shrimps in rainy seasons, and raises brackish-water shrimps in dry seasons and periods of saltwater intrusion.

The project

The first phase is to restore the natural sedimentation process to allow the mixed rice paddies to be fertilized naturally by shrimp manure and nutrient-rich flood sediment. Current practices and associated infrastructure have disconnected the river channels from the floodplain thus most fields are not flooded by river water in the delta notably to avoid the effect of chemicals and pathogens. By reconnecting the paddies and ponds to the natural river channels, which remain relatively clean, healthy sediment can flow into the paddies again.

Separate intake channels for clean water and discharge channels for used water will be created. This will be done using probiotics and photosynthesis bacteria rather than antibiotics and chemicals to reduce toxic ammonia, sulfide and pathogens in the water without consuming oxygen and to decompose organic matter into smaller particles.

A sedimentation and nursery ponds will collect the mud that will be spread onto the soil once a year, raising land levels and naturally fertilizing the soil. Deltares, which is advising on the sedimentation process, estimates that the land can rise by 6 to 10 centimetres per year while the subsidence is two to four centimetres annually, so a net elevation gain in the face of global sea level rise.

Higher yields through responsible production

It is estimated that farmers can increase their shrimp production fourfold: from around 214 kilos per hectare per year in the old model to 800 kilos per hectare per year in the new responsible model. Farmers are expected to increase their income by 3.5 times thanks to the growing international demand for sustainable shrimp and cutting out middlemen by selling directly to Minh Phu.

The farmers will receive training and technical assistance, but also put their own skin in the game. They contribute their land, time and hard work while paying €1,115 in operating costs. Minh Phu will support farmers in pre-financing their inputs (e.g., seedlings etc.) by lending straight to the farmers with the need for collateral and without charging a premium.

“Farmers can increase their shrimp production fourfold: from around 214 kilos per hectare per year in the old model to 800 kilos per hectare per year in the new responsible model.”

Bankable Nature Solutions and Islamic Finance

The goal of Islamic finance is to preserve and circulate wealth by using assets, ownership and property rights in a way that prevents harm and meets the needs of individuals and society in a manner that is just, fair, and equitable, while allowing for wealth redistribution should any imbalances occur.

Maqasid al-Shari’a (MAS), further states that society has the responsibility of caring for private and public interest and keeping others from evil and harm to be able to fully attain societal welfare. Islamic finance believes that money has no inherent value by itself, because money “increases or decreases in value only when joined with other resources for the purposes of productive activities” and that social gains are more important than individual benefits.

It is easy to see how the principles of Islamic finance, described above, can be applied to promote pro-poor development and environmental protection as they are both consistent with the MAS.

The Arab Forum for Environment and Development (AFED) specifically mentions that Islamic finance is ripe for contributing towards SDG 1, 2, 3, 5 and 16 to enable those in the base of the pyramid to get out of the poverty trap. This is due to the deep-rooted history of Islamic finance and “bringing societal good with their rigorous moral and social criteria and emphasis on inclusiveness and broad understanding of business–society relations.

“Islamic finance is ripe for contributing towards SDG 1, 2, 3, 5 and 16 to enable those in the base of the pyramid to get out of the poverty trap.”

The protection of the planet and the environment, climate management and adaptation, are all goals that also conform directly with MAS. The Islamic Declaration on Climate Change also proves the alignment on the need to tackle climate change. The declaration demands the Islamic community to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) and for wealthy nations to “invest in the creation of a green economy.”

The Barriers in the Sector

In practice, the Islamic finance sector has not contributed towards these social or environmental objectives in the way that it was anticipated. The sector has instead invested much below its potential and has been cited as experiencing a potential “mission drift”, with experts demanding much more from the sector to actually contribute towards social and environmental development.

Many experts believe that Islamic development finance has not yet extended itself to “understanding the critical value that ecosystem services and a healthy environment provide to society”. So, whilst the compatibility between Islamic finance and the global goals on climate change, biodiversity conservation, and the environment is high, its implementation is low. The same is believed by those working in ESG in the Arabian Gulf region. While there is clear overlap on social and environmental issues and Islamic finance, little convergence has been realized.

Experts state that while some progress has been made on social dimensions of Islamic finance, “environmental considerations seem to be less of a focus in the Islamic finance industry”. Some banks, such as FAB in UAE, have been following the equator principles and the IFC Performance Standards, however.

Most of the literature cites that the main barriers hindering the Islamic finance sector from investing in the SDGs are lack of regulation, lack of Shari’a governance in green Islamic finance and lack of financial incentives. For example, issuing green products are more complex and costlier than their conventional counterparts. To counter this, markets such as Malaysia and Singapore offer subsidies for green issuance verification to decrease operational costs and increase supply.

There is, however, an evolving vision for the future of Islamic finance. Academia is calling for a sector that promotes shared prosperity and sustainable growth by increasing its support towards social and environmental development and considering financial and non-financial performance in decision-making.

Current State of Sustainable Conventional and Islamic Finance in MENA

WWF commissioned a study to gain insights into MENA regions, as a primer to help it understand how to engage with key stakeholders in the MENA region working in the financial sector (with particular interest in Islamic finance).

The Middle East and North African (MENA) region, is a diverse and culturally rich part of the world, made up of: Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Palestine (the occupied territories of Gaza & the West Bank), Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen. There are approximately 380 million people living in the MENA region and Islam is the predominant religion.

Countries in the MENA region have historically faced many challenges, including war, instability, rapid urbanization, high unemployment, water stress, and harsh climates. Additionally, many countries in the region, particularly the Arabian Gulf countries, have been heavily reliant on fossil fuels to bolster their economy and were deeply impacted by the 2014 drop in oil prices.

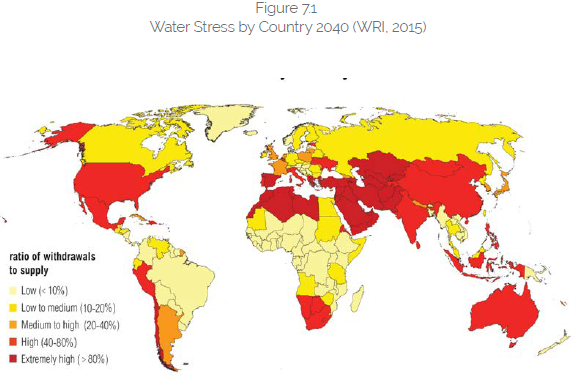

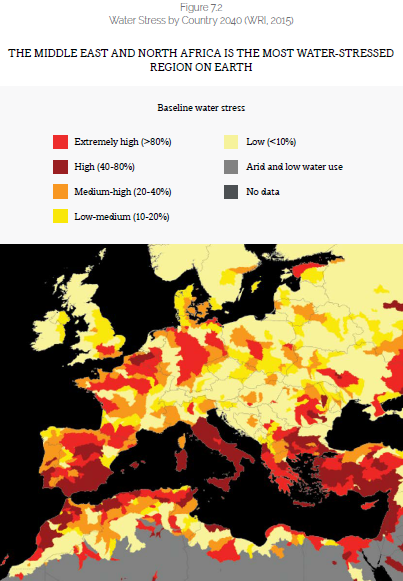

Furthermore, future projections of climate change anticipate rising sea levels, changes in precipitation, and increased temperature, humidity, water acidity and further water stress. More specifically, future projections of climate change show the region facing some of the highest water stress in the world (Figure 7.1), with 12 of the 15 most water-stressed cities in the MENA region as shown in Figure 7.2.

However, many GCC countries tend to publicly focus less on water stress, due to the perception of having high access to water from the infrastructure developed to supply desalinated seawater. This perception has led to GCC countries having a greater focus on in securing new renewable energy capacity.

However, change is taking place across the region. The decreasing cost of renewables, global alignment on the Paris Agreement, need for diversification and pressure from youth on the government to provide higher quality services (education, housing, energy subsidies, safety and jobs) have presented a prime opportunity for the region to re-evaluate their strategies and build a stronger, more inclusive and resilient future. This shift has brought many new stakeholders to the table. The following section will provide a summary on some key advancements in the conventional Sustainable/Green Finance space in MENA. Additionally, countries in the GCC, especially the UAE, have conducted studies on sea level rise and projections are increasingly being accounted for in planning processes. Furthermore, the rate of groundwater and oil extraction will also naturally lead to subsidence and a relative increase in sea levels. There are no public studies on the combined effect of climate change-induced sea level rise and land subsidence.

The UAE

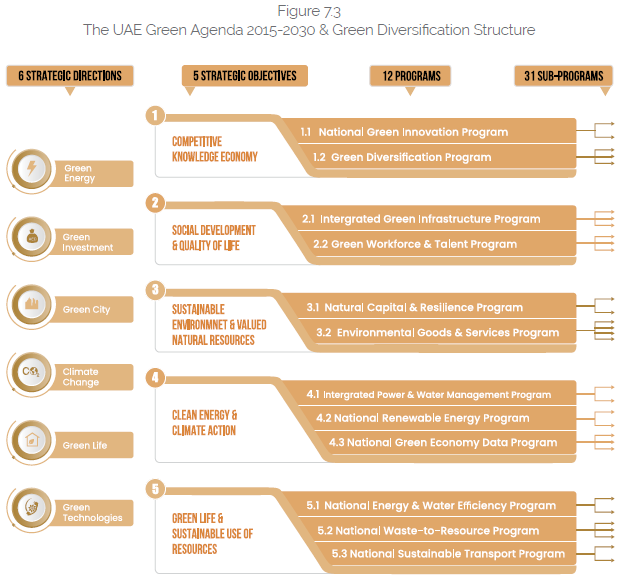

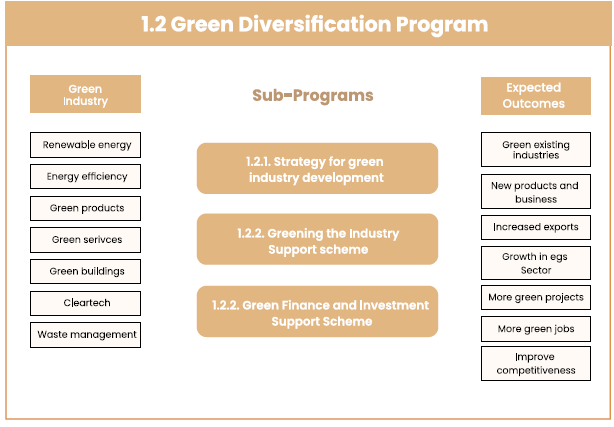

At the federal level, the UAE Ministry of Climate Change and Environment (MoCCAE) has been leading on efforts related to sustainable finance. In 2015, the UAE cabinet adopted the 20152030 Green Agenda as an action plan to implement the country’s Green Growth Strategy. The strategy includes programs on Green Finance and Investment with the objective to “stimulate the financial sector to invest in green projects and business” (Figure 7.3). In 2015, MoCCAE conducted a survey and collected responses from 79 conventional and Islamic institutions to understand their perspectives on green finance. The key barriers listed by institutions to initiating or growing their activities in green finance were:

- enforcement was not adequate;

- that the sector risk was too high;

- payback period was too long; and

- profitable projects were lacking

In 2018, MoCCAE launched the National Climate Change Plan (NCCP) 2017-2050 aimed at tackling climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts in the country, with green finance being listed as a key enabler to the plan. The plan recognizes that green finance is gaining momentum but that “stronger enforcement of policies and regulations in linking bankable projects and financiers is needed”. At the emirate level, MoCCAE partnered with the UN Environment Finance Program Initiative (UNEP FI) in 2016 to launch the Dubai Declaration on Sustainable Finance to convene the finance sector to enable a climate-resilient, inclusive green economy and sustainable development. The signatories are a mix of UAE institutions, both Islamic and conventional.

In 2017, the Dubai Electricity and Water Authority (DEWA) launched a US$27 million fund to finance clean energy and other green projects. The extent to which it will fund projects outside Dubai is unclear at present.

In 2019, the Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC) and the Dubai Financial Market (DFM) launched the Dubai Sustainable Finance Working Group, to “create a sustainable financial hub in the region, particularly in the areas of Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) integration, cultivating sustainable companies and green financial instruments, and encouraging responsible investing”.

Similarly, in January 2019, the Abu Dhabi Global Market also launched the Abu Dhabi Sustainable Finance Declaration, supported by 25 signatories representing a mix of banks, government entities and investment and development authorities. In 2019, the Abu Dhabi Securities Exchange also launched disclosure guidelines for all listed companies to report on ESG, which are mapped according to the following UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Water (SDG6), Climate Action (SDG13), Energy (SDG7), Responsible Consumption & Production (SDG12), Reduced Inequalities (SDG10), Gender Equality (SDG5), Good Health & Well-Being (SDG3), Decent Work & Economic Growth (SDG8) and Peace Justice & Strong Institutions (SDG16).

In January 2020, the ‘UAE Guiding Principles for Sustainable Finance’ was launched by: Abu Dhabi Global Market; MOCCAE; the Central Bank of the UAE; the Insurance Authority of the UAE; the Securities and Commodities Authority; the Dubai Financial Services Authority; the Dubai Islamic Economy Development Centre; the Abu Dhabi Securities Exchange, Dubai Financial Market and Nasdaq Dubai. The principles were developed to boost the implementation of sustainable finance, defined broadly as ESG integration, in the UAE’s financial sector and equally to Islamic institutions and Shari’a-compliant entities.

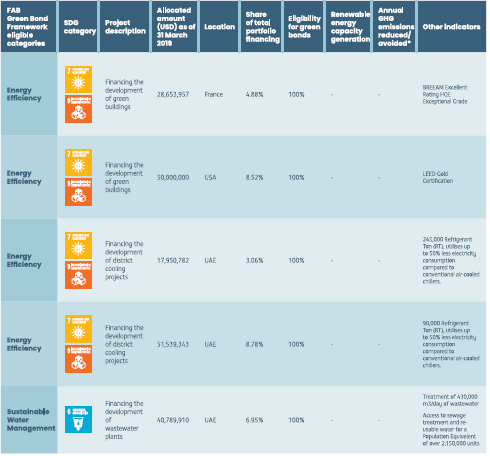

In 2017, the first green bond of the region was issued for US$587 million by the First Abu Dhabi Bank (FAB). The green bond aims to finance projects both in the UAE and internationally with the objectives of addressing climate change through investing in renewable energy, energy efficiency and sustainable water management (Figure 7.4). Currently the bond finances project in the UAE, Morocco, France and the United States and finances projects that meet sustainability criteria which include: sustainable management of living natural resources, terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity conservation and climate change adaptation, amongst other.

Use of Proceeds of FAB Green Bond (FAB, 2019)

In 2017, Emirates NBD launched a Green Auto Loan to UAE residents to promote electric and hybrid cars. The bank offers applicants to waive the processing fee and offers half a percent reduction on applicable loan rates to stimulate the use of the green loan.

Other MENA Countries

In 2016, Morocco launched in National Roadmap for Sustainable Finance strategy, which aims to develop sustainable finance instruments and products, ensure disclosure, extend governance to ESG, promote financial inclusion, and build capacity in sustainable finance. Since then, Morocco has developed guidelines for green and social bonds, guidelines on ESG and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) reporting and have authorized two Socially Responsible Investment (SRI funds).

Additionally, the region’s biggest sovereigns (Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, UAE and Qatar) have signed onto the One Planet Sovereign Wealth Funds Framework and are part of the founding working group to integrate climate change considerations in investments. While there are some emerging examples of action, there is no coherent region-wide strategy or policy to enhance sustainable finance (e.g., like the European Union). Sustainable finance can, therefore, still be considered as a new and emerging topic in the MENA region as regulatory infrastructure and policy framework are beginning to be developed. Furthermore, ‘green Islamic finance’ would naturally be a subset of this broader movement in sustainable finance and, therefore, can be considered as being in its infancy. For example, a review Saudi Arabia’s contribution towards the SDGs and the Saudi Vision 2030 yielded in no tangible actions in the area of sustainable finance. Most of the other countries in the region are recipients of development assistance and climate funds for energy efficiency and renewable energy projects.

The Opportunity for Islamic Social Finance in MENA

There are multiple terms that lend themselves to the intersection of Islamic finance and social and/or environmental development. However, the opportunity of Islamic finance with the SDGs, ESG integration and impact investing is of particular interest here.

It is easy to see how the principles of Islamic finance can be applied to promote pro-poor development and environmental protection as they are both consistent with the MAS. As stated above, Islamic finance has for contributing towards SDGs 1, 2, 3, 5 and 16 (please refer to the figure on pg. 191) to enable those in the base of the pyramid to get out of the poverty trap. This is due to the deep-rooted history of Islamic finance and “bringing societal good with their rigorous moral and social criteria and emphasis on inclusiveness and broad understanding of business–society relations.

The protection of the planet and the environment, climate management and adaptation, are all goals that also conform directly with MAS. The Islamic Declaration on Climate Change also proves the alignment between Islamic scholars on the need to tackle climate change. The declaration demands the Islamic community to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) and for wealthy nations to “invest in the creation of a green economy”. However, as stated earlier, the Islamic finance sector in practice has not contributed towards these social or environmental objectives in the way that it was anticipated. The sector has instead invested much below its potential and has been cited as experiencing a potential “mission drift”, with Islamic economists demanding much more from the sector to actually contribute towards social and environmental development.

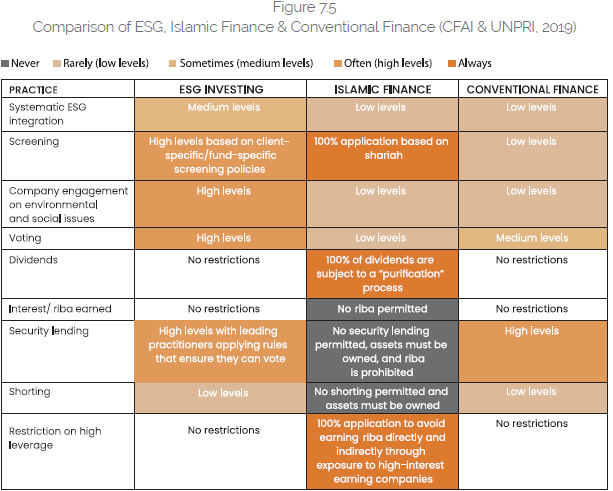

Many experts believe that Islamic development finance has not yet extended itself to “understanding the critical value that ecosystem services and a healthy environment provide to society”. So, whilst the compatibility between Islamic finance and the global goals on climate change, biodiversity conservation, and the environment is high, its implementation is low. The same is believed by economists working in ESG in the Arabian Gulf region. While there is clear overlap on social and environmental issues and Islamic finance (Figure 7.5), little convergence has been realized. Experts state that while some progress has been made on social dimensions of Islamic finance, “environmental considerations seem to be less of a focus in the Islamic finance industry”.

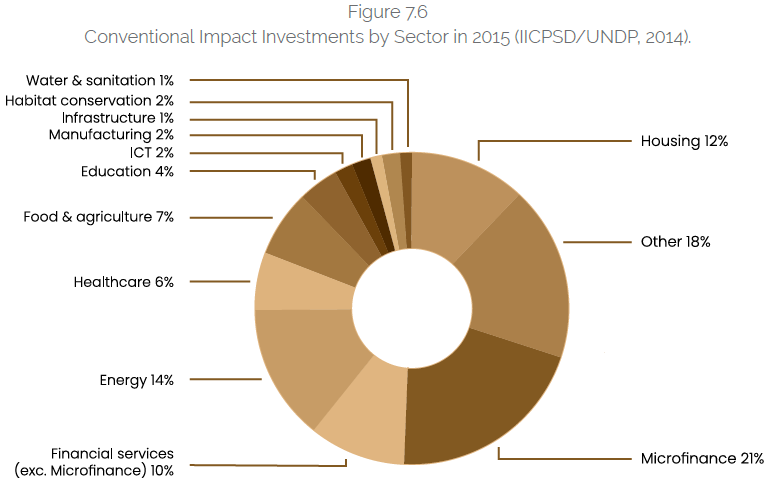

In similar vein, the impact investing space has also been positioned as having the potential to intersect with Islamic Finance. Impact investing has the potential to fund an estimated $1 trillion towards the SDGs, but its investments towards water and sanitation and habitat conservation are still small, at 1% and 2% invested respectively (Figure 7.6). However, despite the synergies between Islamic finance and impact investing the interactions between the two sectors is limited.

“Despite the synergies between Islamic finance and impact investing the interactions between the two sectors is limited.”

Most of the referred literature cites that the main barriers hindering the Islamic finance sector from investing in the SDGs are lack of regulation, lack of Shari’a governance in green Islamic finance and lack of financial incentives. For example, issuing green products are more complex and costlier than their conventional counterparts. To counter this, markets such as Malaysia and Singapore, offer subsidies for green issuance verification to decrease operational costs and increase supply.

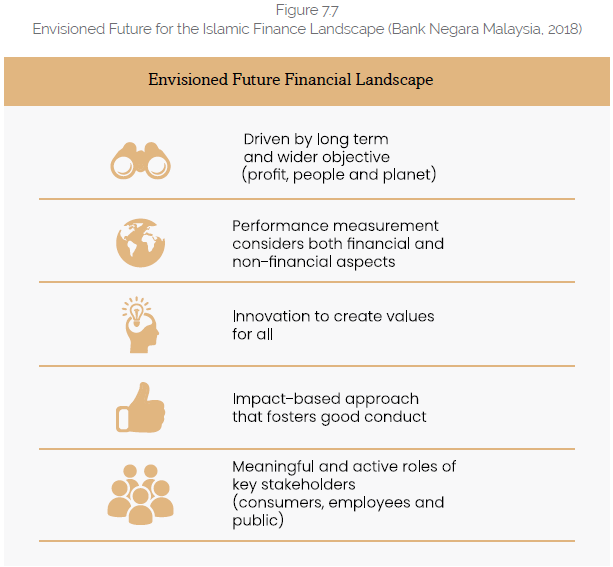

There is however an evolving vision for the future of Islamic finance. Academia is calling for a sector that promotes shared prosperity and sustainable growth by increasing its support towards social and environmental development and considering financial and non-financial performance in decision-making. (Figure 7.7).

Envisioned Future for the Islamic Finance Landscape (Bank Negara Malaysia, 2018)

Modelling the Opportunities for Islamic Social Finance

While the climate and development sectors are a natural fit to the landscape in which Islamic finance is permitted to operate, financial proposals around such projects inevitably need to be structured following Islamic principles as well to attract participation from custodians of Islamic capital in both government and the private sectors.

Introducing Dutch Fund for Climate and Development – Model for Islamic Social Finance

While there may be multitude of opportunities suitable for Islamic finance, Dutch Fund for Climate and Development provides an exceptional and unique preposition that Islamic finance sector can take the lead from and showcase a very powerful implementation model of MAS and SDGs in a commercially viable and socially impacting manner.

Dutch Fund for Climate and Development – A Powerful Strategy of Sustainable BNS

As noted earlier, the extraordinary scale and urgency of the climate crisis has led to an increase in global flows of climate-related investment in recent years – resulting in real changes across the world. But global climate finance remains well short of the overall target and most of the funds are focused on mitigation. Annual flows to projects with an adaptation impact in developing countries continue to lag far behind. Blending public funds with private sector finance can help close the current funding gap and support the most vulnerable groups in addressing climate and development challenges. High-quality projects that bring a development, as well as a financial dividend, are needed to ensure such blending is effective.” – this is the motivation behind the establishment of Dutch Fund for Climate and Development (DFCD) that was launched in 2019, salient features of which are reproduced below:

- The FMO-led consortium aims to deliver such projects through innovative management of the DFCD, unleashing a flood of new climate-smart investments.

- The alliance of FMO (The Dutch development bank), CFM (Climate Fund Managers), SNV (a not-for-profit international development organization, working in Agriculture, Energy, and Water, Sanitation & Hygiene) and WWF harbor a wealth of international expertise in finance, banking, social development and environment.

- This expertise is deployed to construct a pipeline of high-quality, bankable projects to contribute to (i) real development impact in climate-vulnerable communities; (ii) deepen resilient economic growth; and (iii) enhance the adaptation and mitigation efforts in developing countries.

- The DFCD focus is on a set of high-impact investment themes within four key Rio Marker sectors: – water, agriculture, forestry and environmental protection – all of which are critical to tackling climate change and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. The chosen focus areas are where there is the most pressing need for investing in low-carbon, climate-resilient projects in vulnerable countries. They also offer significant opportunities for impact and improving development outcomes and are consistent with the priorities of developing countries as stated in their Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement. These themes also have a clear link to Dutch climate diplomacy efforts and core strengths of Dutch business: exports of technology, knowledge and services in water infrastructure, and agriculture.

- The DCFD also enhance the health of critical ecosystems – from rivers to tropical rainforests, marshes to mangroves. This will help protect communities and cities from the increasing frequency of extreme weather events and benefit the vanishing biodiversity that provides people with water, food and medicine – and so much more.

- The high impact investment themes are: (i) Climate resilient water systems and freshwater ecosystems: drinking water and sanitation infrastructure, restoration and sustainable management of wetlands, headwaters and floodplains; (ii) Boost food security with climate smart agriculture: funding more sustainable, efficient and productive approaches from

smallholder farmers to agri-business; (iii) Forestry for the future: promoting afforestation and reforestation; and (iv) Protecting the environment, protecting people: restoration of ecosystems, such as wetlands and mangroves, which are nature’s best defences against extreme floods, droughts and storm surges.

- The DFCD is structured with three separate but operationally linked facilities, each with a specific sub-sector focus and role across the project lifecycle: the Origination Facility, the Water Facility and the Land Use Facility.

- Managed by WWF-NL and SNV collectively, the Origination Facility is positioned exclusively for project identification and (pre-)feasibility development activities with a cross-DFCD thematic subsector focus. This window seeks to leverage the landscape strategy for activity sourcing and develop opportunities into viable business cases for the two investment windows. The Origination Facility provides grant funding and TA for its activities.

- An Origination Facility is the engine of this transformative DFCD, turning embryonic ideas into bankable business cases. Working with local companies and stakeholders, bankable projects are developed using a landscape approach in which building the resilience of an entire ecosystem will benefit the communities and businesses that depend on them. The facility will develop 35 projects to the stage where they can then be picked up by one of the DFCD’s other two finance facilities for further development, matchmaking and investment, or undertaken by others.

- Managed by CFM, the Water Facility targets investments that have graduated from the Origination Facility in sectors related to water and sanitation infrastructure, as well as environmental protection. The Water Facility contributes to the development, construction and operational phases of investments. To achieve this the Water Facility provides development grants, equity for construction and operational debt to projects. It utilizes the proven fund structure of Climate Investor One and targets a €50 million Development Fund, a €500 million Construction Equity Fund and a €500 million Refinancing Fund.

- The Water Facility also source opportunities from CFM’s external networks and provides post-construction phase community development and TA. The Water Facility focuses on providing construction equity into water infrastructure and environmental protection projects. By providing risk-bearing equity capital, it will be able to crowd-in further investors to help ensure that 30 projects are fully financed and implemented.

- Managed by FMO, the Land Use Facility targets investments that have graduated from the Origination Facility in sectors relating to agroforestry, sustainable land use and climate-resilient food production. The Land Use Facility has at its disposal the full range of financial instruments offered by FMO to provide growth finance to companies, including grants, equity and debt.

- It also sources opportunities from FMO’s external networks and provides post-construction phase community development and TA financing. The Land Use Facility will provide growth finance by deploying a range of financial instruments to overcome barriers to private sector investment in climate-smart agriculture and forestry projects – with the aim of ensuring 25 projects reach financial closure.

- Using these facilities, DFCD will leverage €500 million–€1 billion of private finance over the lifetime of the DFCD (until 2037), generating a significant multiplier effect with the €160 million from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. As these funds are revolving and keep growing, they ensure financial sustainability and real impact at local and global scale. The Consortium also expects all projects to be 50% co-funded, while several Origination Facility projects will be very suitable for external public sector funding – and hence will mobilize these funds as well.

- The Consortium is governed through a DFCD Advisory Board, which role is primarily to: (i) monitor/report/evaluate the implementation & progress and financial & impact results of the three Facilities; (ii) act as a general forum for communication; and (iii) monitor significant trends in global climate policy & finance and assess their relevance for the DFCD.

Islamic Fund for Climate and Development – A Model Proposition

Given that most Islamic financial institutions are in the GCC, there is therefore an important opportunity to highlight the link between water stress, climate vulnerability and the role for Islamic financial institutions (among other stakeholders) to reduce these risks.

The study referred to in preceding gave WWF insights into Islamic finance sector, as a primer to help it understand how to engage with key stakeholders in the MENA region working in Islamic finance sector with a view to having them take part in initiatives similar to the DFCD. The study identified opportunities and synergies between Islamic finance [including, Islamic Social Finance (zakah, sadaqa, waqf and Islamic microfinance)] and the BNS conservation and climate-related projects. Study highlights useful insight into the size and significance of IsBF industry which is currently estimated to have about US$2.941 trillion of assets (close to half of which is in the GCC alone or close to 2/3rd in the MENASA region including GCC and close to 1/4th in South-East Asia region). The study also revealed that custodians of Islamic capital remain keen and interested in participating commercially viable BNS projects. This interest has been identified amongst a vast variety of Islamic finance stakeholders including Islamic financial Institutions, sovereign/multilateral organizations, family offices, high-net-worth individuals, fund managers, and philanthropic organizations.

WWF and Ajman University Center for Excellence in Islamic Finance (AU-CEIF) have jointly thought through the possibility of creation, launch and promotion of an Islamic version/tranche of DFCD – ‘Islamic Fund for Climate and Development (IFCD). Following the model and approach of DFCD and leveraging on the expertise and track record of its Consortium members, IFCD has the potential to offer a market-leading opportunity to Islamic finance sector in BNS space. While creation of IFCD will require Shari’a structuring, compliance, and governance system; consortium should well be able to manage and run such a strategy with support and partnership of various stakeholders of Islamic finance sector.