Introduction

Instigating a debate in Islamic finance can oftentimes excavate uncomfortable truths for one of the parties involved. Undeniably, this has proven to be the case with the envisaged launch of the Goldman Sach’s ‘mile-stone’ Global Sukuk.

Most Islamic institutional investors indeed wondered from the sidelines about the sheer audacity of a conventional banker at the core of, if not partly responsible for, the present global crisis, launching a USD 2 billion sukuk without however publicly divulging prospected rates of return and with an implicit claim to the so-called ‘Sukuk Premium’. With the current sukuk market being far too shallow, Shari’a-sensitive investors are often in need of investable financial paper, that they are willing to accept lower returns than their conventional counterparts. Some voices considered it a good idea for conventional banks to enter the Islamic finance space and to tap the available Islamic resources in a compliant way, hoping it could end up in overall acceptance and recognition and even in a considerable boost of the Islamic market itself. Before even determining which of these opposing sides has a stronger argument, it is more appropriate to look into the structure of the sukuk thereby going to the heart of the matter. A western supermarket can sell meat, which would only be acceptable to a discerning Muslim population if it is halal. Likewise, the Goldman Sach’s Global Sukuk can only be acceptable if the structure is Shari’a compliant. A closer inspection however reveals issues of considerable concern.

The base prospectus²: a plain vanilla murabaha facility

On Nov 3rd, 2011, the rating agency Moody’s assigned a (P)A1 to the Goldman Sachs’s sukuk program. Fitch considered it to be A+/F1+ on Oct 19th, 2011 and placed the rating on Rating Watch Negative. The multi-currency sukuk program is to be issued by Global Sukuk Company Ltd, a Cayman Islands-domiciled SPV, and may include several currency denominations including UAE dirhams, US dollars, Saudi riyals and Singapore dollars with allocations to be determined by Goldman Sachs.

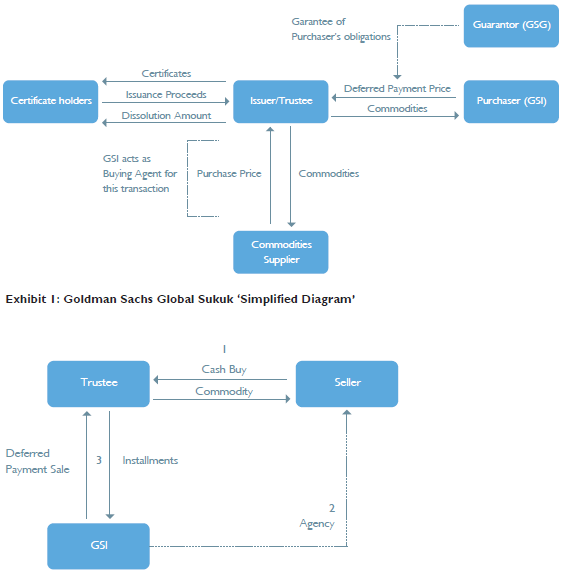

So how did they determine the rating of the sukuk? Islamic financial structuring often makes use of graphics to explain the flow of monies and underlying contracts to the interested investors. The Base Prospectus makes no exception to this. (Exhibit 1)

As Exhibit 1 might still be slightly inaccessible for some, we will insert a further simplified model, that shows the true nature of the actual transaction as conveyed by the Base Prospectus. (Exhibit 2)

In the regular murabaha-to-the-purchase-order, the IFI (Trustee) will buy a specific asset at specific conditions to sell it down to the Client (GSI) at a Purchase Price plus a pre-agreed markup. GSI will function as Agent of the IFI (Trustee) and will choose the asset and negotiate price and other modalities. This is to ensure that the right assets/materials are purchased at exactly the desired conditions.

The Base Prospectus repeats several times: “whereby the Trustee will, at the request of GSI, use the proceeds of the issuance of the Series to purchase certain commodities from a third party Seller on im- mediate delivery and immediate payment terms and will immediately sell such commodities to the GSI on immediate delivery terms but with payment on a deferred basis.”³ Dar Al-Istithmar, the Shari’a advisor to the transaction, added that the documentation “clearly shows that Trustee, as seller, sells the commodity to GSI, as purchaser.” and further that: “Once the commodity is sold to GSI, its then at GSI’s discretion to do what it wants to with the commodity”. The structure appears to follow the widely used practice of the murabaha-to-the-purchase-order facility.

It was also proclaimed by those who structured the transaction that the legal documents had been reviewed and approved by leading scholars in the Islamic finance industry in order to quell further inquiries. However, despite the apparent conformity to Shari’a, the structure requires a second leg, to effectuate the cash flow and produce the required profits to make the sukuk of value. This originated the ‘tawarruq-debate’, which has far greater implications on the Shari’a authenticity of the product.

1. The IFI/Financier (the Trustee as holder of the sukuk funds) buys with cash from the Seller the agreed-upon assets/commodities

2. The Client (GSI) is in this acquisition transaction the exclusive Buying Agent of the IFI/Financier (Trustee)

3. Using a ‘Plain Vanilla’ Murabaha, the IFI/Financier (Trustee) sells that commodity down to the Client (GSI) on a deferred payment basis (cost + markup) and the Client (GSI) settles the deferred payment as the instalments come due

The individual ‘plain vanilla’ Murabaha transactions are part of a ‘plain vanilla’ USD 2 billion Murabaha Facility between GSI and the Trustee.

Exhibit 2: ‘Plain Vanilla’ Murabaha-to-the-Purchase-Order MPO Facility

About the nature of tawarruq

The Client (GSI) is likely to sell the commodity immediately down for cash. Then the Client (GSI) ends up with zero commodities as these would have been sold, with cash at hand from the revenue of sale and a deferred payment from the initial acquisition to be paid to the IFI (Trustee). Thus, in conclusion, this would be money in the pocket against a deferred payment with a markup thereby resembling a tawarruq structure (cash procurement). If the IFI (Trustee) organizes the scheme – as we will see hereunder – then this is an ‘organized tawarruq’. Opinions on its permissibility thereof are divided.

It may be assumed that the GSI does not intend to hold on to the USD 2 billion worth of commodities as bought from the Trustee, but intends to sell them down for cash and then use that cash for other operations. The Base Prospectus actually states: “Use of Proceeds

– The net proceeds of each Series issued under the Programme will be applied by … GSI … for its general corporate purposes and to meet its financing needs”.

It is clear that there will be a second leg attached to the initial murabaha and that this second leg was intended from the beginning of the transaction. It makes sense that a USD 2 billion second leg will be organized’ seamlessly. The Base Prospectus actually regulates the modus operandi thereof: “Upon completion of the sale of the Commodities by the Trustee (in its capacity as Seller) to the GSI, the latter may hold the Commodities as inventory or elect to sell the Commodities in the open market provided that where GSI elects to sell the Commodities, it shall sell the Commodities to a third party buyer that is not the initial Seller”. But would that mean it is unlawful? Dar al Isthimar have opined that once the commodity is sold to GSI, it’s then at GSI’s discretion to do what it wants to with the commodity” As it would be the case for any other Client, for that matter. However, selling something ‘knowingly and intentionally’ in order to help organize a cash flow against a markup for a deferred payment facility is different to ‘ unknowingly and unintentionally’ be involved in such a scheme. It would appear that GSI is selling commodities ‘knowingly and intentionally’.

The tawarruq is a simple cash generator whereby (1) cash is (2) converted to a commodity with a deferred payment and then (3) back to cash. This is deemed lawful as such by most scholars. However, as stated above, the OIC Fiqh Academy has declared it unacceptable for an IFI to take part in the organization of such cash- against-deferred-payment-with-profit structures (actually to be understood as cash against deferred payment and interests).

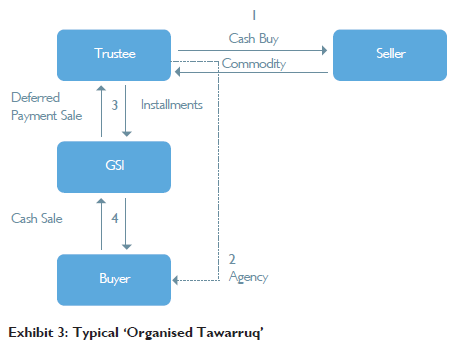

Traditionally, the IFI used to offer the tawarruq as an organized package (hence ‘organized tawarruq’). The Client only had to sign some paperwork in order end up with cash and a deferred payment at a cost. A Selling Agency in favor of the IFI ensured that all would go as to plan. The client was reduced to a mere spectator ‘with benefits’ (see Exhibit 3).

In a typical organised tawarruq, the IFI is involved in the second leg following the initial murabaha: it operates as Agent for the Client in order to sell the commodity down to the Buyer. This is as a facilitator (the Client usually has no idea about how to buy/sell commodities) and to ascertain that the Client walks out with the desired amount of money against the expected cost.

The GSI variation on the ‘organised tawarruq’ theme

Now let us have a look at the probable intention hidden in the GSI-variation.

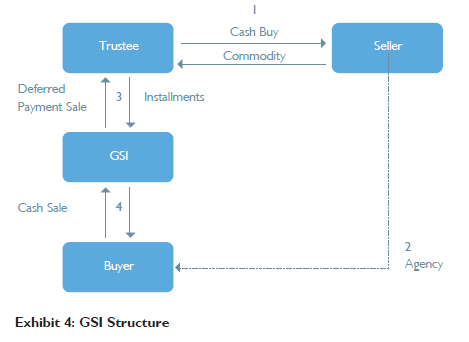

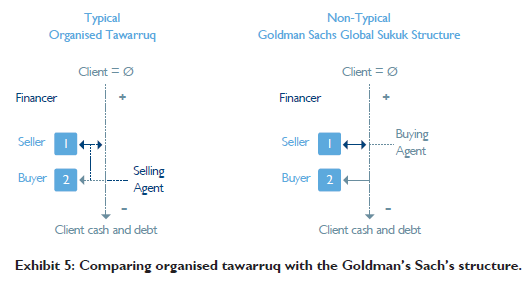

Surprisingly, the IFI (the Trustee) is NOT involved in the second sale. There is no agency. Therefore, this at first sight does not appear to be a regular organised tawarruq, but a regular Tawarruq. This offered Dar Al-Istithmar the opportunity to state that one has no idea what will happen afterwards and therefor bears no responsibility.

But there is another difference with the typical organized tawarruq. Except for the legal issues (signing of papers and transfer of legal title), the Trustee is not involved in the first buy. This operational right is exclusively transferred to the Client (GSI) through an exclusive agency agreement.

GSI is actually ‘organising’ the two-legged structure by itself and reserves full control by also organizing the IFI (Trustee) and controlling its behaviour. The tables are simply turned: control is shifted from the IFI (Trustee) to the Client (GSI). It is the old substance .v. form de- bate bubbling up again. The Trustee adds no real value to the structure and serves to provide a degree of authenticity to the product

Going through the structure diagrammatically will help us understand what really happens.

The Trustee is not an existing, independent IFI but an empty Special Purpose Vehicle SPV that has been incorporated by GSI who has fully restricted its capabilities to act. The full murabaha facility, the murabaha conditions and the exclusive agency conditions have been pre-set and dictated by GSI.

GSI indeed is capable to run both legs of the structure all by itself. If it were not for the need to ensure formal Shari’a compliance, the Trustee and the murabaha structure would not be there at all. The SPV is a pure complaisance intermediate. This inversion of powers and organization is fundamentally different from the regular murabaha facility where the Financier/IFI is in control, and where (A) the Client (as another financier) will use the proceeds to extend compliant financing to their underlying clients (i.e. generate liquidity); or where (B) the Client (as commercial entity) either uses the proceeds to buy real economy assets or generate cash for use in tangible operations as approved and known by the Financier. Possible ribawi tainting is controlled to acceptable levels and clients in haram industries are simply excluded. In this situation, Goldman Sachs is a conventional ribawi lender without an Islamic window, and is involved in financing haram industries. Thus special caution is required. The statement that GSI is not a conventional bank but an investment bank12 is disingenuous. and creates misplaced trust, since GSI is a ribawi bank. It partakes in activities and investments in haram industries. It is the purveyor of interest-based and speculative products, such as derivatives, which hardly garner Shari’a approbation. The argument that as an investment bank and proprietary commodity trader, GSI will use any returns solely on Shari’a-compliant financing is presumptuous at best. Financial structuring and income generation of a conventional investment bank would make any Islamic investment banker aghast at the ribawi and haram twists and turns. The traditionally ‘organised’ Client/GSI becomes the ‘organiser’ and the Financier/Trustee is reduced to a mere puppet for signatures only, but nevertheless plays along. Time will tell if such inversion in the organisation, surrender and declared innocence are sufficient to escape the OIC Fiqh Academy ruling and if Islamic scholarship is willing to validate such a transaction.

The use of the proceeds

After the second leg of the transaction, we cannot be sure where the USD 2 billion goes. It becomes an accounting entry and goes into the pool for a conventional banker, to be used “only, for its general corporate purposes and to meet its financing needs”. “That’s it.” Without suggesting any intentional wrongdoing on the part of GSI, the permutations that are available for a non-Islamic, creative mindset, to utilise the funds for Shari’a non-compliant activities is significant and far outnumbers the possibilities for Shari’a compliant investments.

The apparent absence of the isolation and independence of the monies/activities in an Islamic window/unit is of serious concern, especially since one cannot find in the Base Prospectus:

1. either a written commitment from GSI to treat the proceeds of the transaction in a fully compliant way; and/or

2. a written commitment from GSI to fully isolate the proceeds from funds used by a conventional banker; nor

3. a statement from the Shari’a Board that there is constant monitoring, reporting, isolating, or cleansing of the funds. The statement that whatever happens with the commodities after GSI completes the murabaha is their business is alarming in this respect.

Failing to ring-fence the monies within a conventional bank, irrespective as to whether it is an investment bank, could create a situation where there is no guarantee that the sukuk and the sukuk holders will not be serviced with ribawi revenues (eventually even originating from haram industries). This is problematic for any Shari’a-sensitive investor.

It has been argued that money does not smell and has no color (in the sense that sin does not stick to it when transferred – as it does to pork meat for in- stance) and that the Prophet (pbuh) also entered into business with non-believers paying with non-compliant proceeds. That may be true, but it is far too simplistic an argument to be credible. There is no evidence suggesting that the Prophet, knowingly, extended a credit facility to a non-believer in order for the latter to utilise these amounts on haram transactions and to use the proceeds of these activities to serve as payback. To put it differently: selling a car to a non-believer is of a different nature than extending a credit line to a gambler in order to allow him to build and operate a casino and then declare the proceeds as acceptable. Scholars and regulators need to reflect carefully on these nuances.

Arguably, this transaction does not deepen the Islamic finance pool, but drains it of its already limited resources. Though still questionable, it would have nevertheless been a beneficial step forward if GSI had isolated the receivables from its haram activities and committed to use them for halal purposes and in compliant structuring under the supervision of a Shari’a Supervisory Board.

Listing on the Irish stock exchange

Further concerns relate to the listing on the Irish Stock Exchange. The official position is brief: “…the offering circular clearly states in several places that the certificates can only be traded on a spot basis and at par value if they are to be Shari’a compliant … hence the listing can, practically speaking, only have a taxation and regulatory benefit without impinging on Shari’a principle in any manner.”

The only practical intention and result from a listing is that financial instruments are actually traded and that ‘practicality’ will materialise where sukuk holders will trade supposedly non-tradable murabaha sukuk on the Irish Stock Exchange at a discount. Hence, this creates a ribawi situation.

By opening the door to possible interest-bearing situations, a strong precedent might be set towards new and dubious transactions. Before long, non-tradable Sukuk will be tailored to appeal to non-compliant investors, maybe even targeting haram business and generating monies used for ribawi and non-compliant purposes and we might even see parallel markets develop.

With a non-compliant sukuk market underscored by non-tradable sukuk, this potential parallel market may outgrow the real Islamic market16. Worryingly, it may set the pace and dictate conditions and market evolutions. Such a parallel market can hardly be the intention of Islamic finance.

Non-compliant investors should accept all the pre-set conditions of Islamic finance or stay out. To keep the market consistent, it appears to be unacceptable that the rights and duties of parties should depend on their religious conviction. Those rights and duties should be incorporated in the paper and all issuers and investors should abide by those rules and not offer non-compliant solutions, whatever the cost.

Conclusion

Goldman Sachs’ ‘milestone’ Global Sukuk appears to adopt a controversial structure, specifically geared towards the needs of the non-compliant user and the creation of a secondary market leading to opportunities for riba. This is to be regretted. It would have been optimal if instead of the apparent plain vanilla murabaha facility, a non-organised (and therefore for most Scholars permissible) tawarruq was created ;

In reality, the structure boils down to a non-typical variation of an organised tawarruq – where the ‘organised’ (Client / GSI) becomes the ‘organiser’ and where the ‘organising’ Islamic banker/financier (Trustee) becomes the ‘organised’ puppet in the transaction but decides to play along. The absence of guaranteed isolation of funds in the hands of a conventional banker appears to be even more troublesome. The sukuk holder may be serviced by the revenues out of unclear income streams that might be riba generating or even stem from haram industries. Whilst this, at first sight, may not be an issue, it becomes questionable when the initial transaction serves the sole purpose of inducing the haram carrousel in the first place.

The listing on a stock exchange of non-tradable murabaha sukuk is the most perplexing act. To open the door to parallel sukuk markets (unfortunately, conventional traders will trade the paper on the stock exchange at a discount in order to generate profits) for the sake of tax advantages is bound to end up being controversial and is extremely debilitating for the Islamic finance industry. One point which has not been discussed is the use of the debt-based murabaha sukuk. This type of sukuk became controversial following the criticisms of Muhammad Taqi Usmani. It was expected that the sukuk would become obsolete in the envisaged evolution of the market from asset-based to asset-backed sukuk but the use of such a sukuk resurrects the debate once again.

It may be expected that – given the perceived necessities of the present global financial crisis – the hunger of conventional banks for Islamic funds by using the easy-to-go tawarruq structure may be convenient and necessary. An outflow of monies generated in a Shari’a-compliant manner for use in the conventional sphere (helping to sustain or even inflate the synthetic financial markets) could be the consequence, coupled with an influx of non-compliant structuring techniques. Allowed trading on the secondary markets would only enhance the attraction.

The benefits of this apparent unrestricted liberalism for the Islamic capital markets (in return for an expected bigger volume in issuances, global acceptance as a viable alternative, bigger compliant [and non-compliant] secondary markets) remains to be seen. It may be expected that ‘conventional sukuk’ – not interested in developing compliant and thus more restrictive standards – might strive for the bottom of the market (and force Islamic finance to stay there in order to compete) rather than show the way to more compliancy. All this may be prevented if – as could be the case in the Goldman Sachs Global Sukuk – Islamic financial resources is managed through compliant structures, which consider all aspects of the transaction: from the way the original investment is generated, the use of funds by the client, and finally the possible trading of tradable sukuk on a [hopefully compliant] stock exchange. Islamic financial scholars and regulators have an important strategic task at hand. The Goldman Sachs Global Sukuk makes this clear.